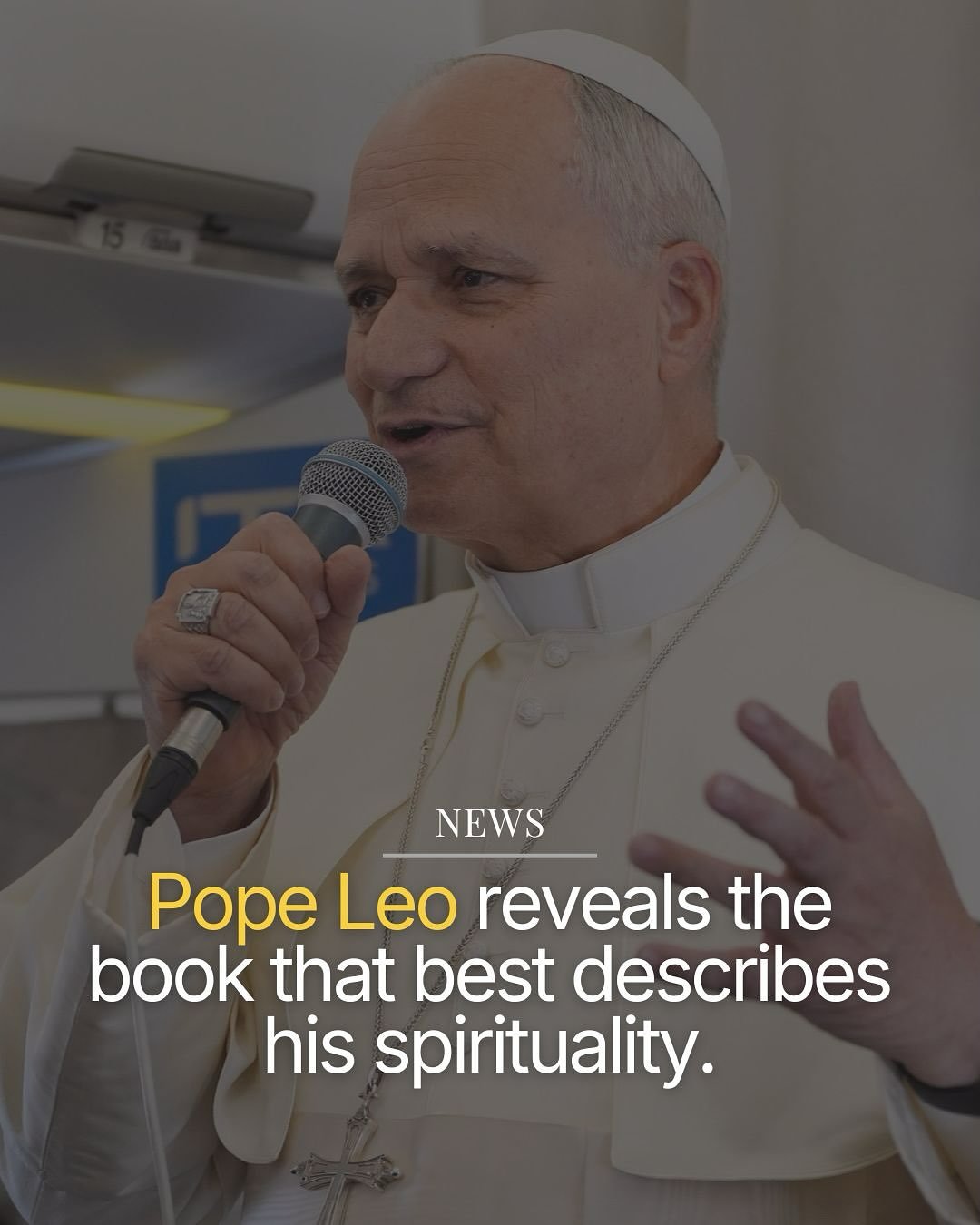

A Clear, Easy-to-Read Translation of G.K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy

G.K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy is the first Modern Saints release for a reason. This whimsical defense of the faith is widely considered a top-ten Christian book of all time and is as relevant now as the day it was written. If you are a fan of C.S. Lewis (or just a fan of good books), you will love this modern, vibrant take on a pop-philosophy classic.

“I’ve read this version twice and enjoyed it both times. When I read it originally it felt like reading Mandarin, but this version is like you knew Mandarin and translated it.”

– Allen Harrell, Book Reviewer

Explore Our Books

-

![A person holding a book titled 'Confessions: a modern translation' by St. Augustine, featuring a green pear with a bite taken out on the cover, near a window.]()

Confessions

St. Augustine’s honest, unfiltered account of love, longing, struggle, and unexpected grace.

-

![Book titled 'The Imitation of Christ' by Thomas à Kempis, translated by Peter Northcutt, placed on a dark wooden surface.]()

The Imitation of Christ

Thomas à Kempis' classic devotional on humble discipleship, guiding you to align your life with the heart of Christ.

-

![Person holding a book titled 'The Practice of the Presence of God' by Brother Lawrence, translated by Peter Northcutt.]()

The Practice of the Presence of God

Brother Lawrence’s short guide to simple spirituality, helping you live every moment in God’s presence.

-

![Book titled "The Pilgrim's Progress" by John Bunyan on top of a gray notebook and a brown folder, with a black pen resting on the notebook, all placed on a wooden surface.]()

The Pilgrim's Progress

An exciting take on John Bunyan’s adventurous allegory, inspiring you to journey boldly toward a life with God.

-

![On the Incarnation]()

On the Incarnation

St. Athanasius’ profound exploration of the mystery of Christ, revealing the transformative power of the Incarnation.

-

![A person holds a book titled "The Interior Castle" by St. Teresa of Avila, with a golden key resting on the cover.]()

The Interior Castle

St. Teresa of Avila’s spiritual masterpiece, guiding you on a journey to deeper intimacy with God within the soul's many chambers.

-

![Book titled 'Orthodoxy' by G.K. Chesterton with a gold apple on the cover, placed on a glass table next to a wooden surface.]()

Orthodoxy

G.K. Chesterton’s whimsical defense of the Christian faith, inviting you to embrace the wonder and truth of orthodoxy.

-

![A book titled "Dark Night of the Soul" by St. John of the Cross, translated by Peter Northcutt, is placed on a gray textured fabric surface.]()

Dark Night of the Soul

St. John of the Cross’ profound guide to spiritual transformation, leading you through the trials of faith into the light of divine union.

-

![Person holding a book titled 'The Rule of St. Benedict a modern translation' by St. Benedict, with an illustration of a stained-glass window on the cover, on a green upholstered surface.]()

The Rule of St. Benedict

St. Benedict’s timeless guide to monastic life, inviting you to shape your life around the rhythms of prayer, work, and community.

-

![Book titled 'The Way of a Pilgrim' on a shelf, with a prayer rope in front.]()

The Way of a Pilgrim

The unforgettable journey of a pilgrim who longs to “pray without ceasing.”

-

![Front cover of a book titled "La Práctica de la Presencia de Dios" by El Hermano Lorenzo, translated by Dr. Marlee Northcutt, published by Modern Saints.]()

La práctica de la presencia de Dios

Experience Brother Lawrence’s sage wisdom in this new Spanish translation!