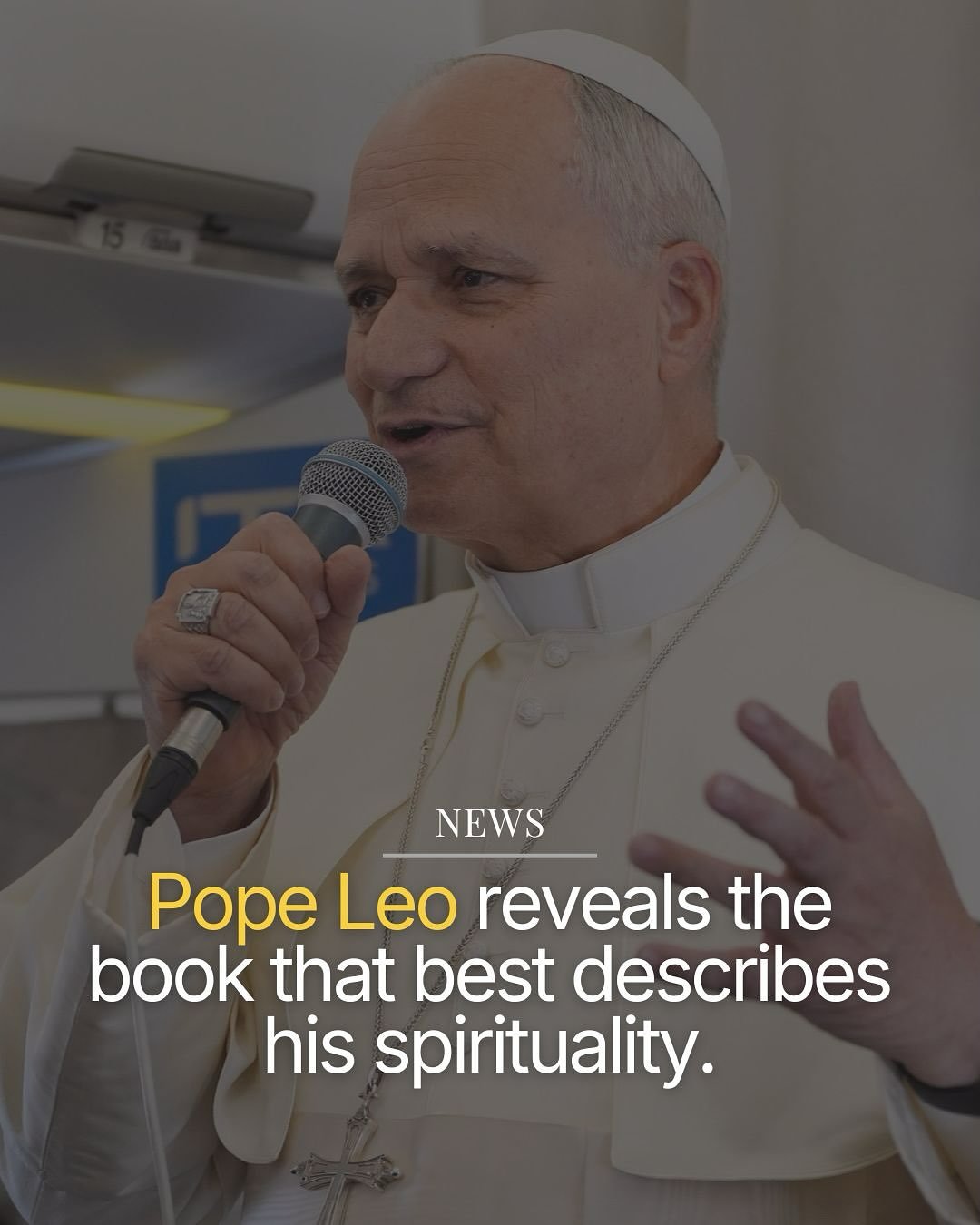

A Clear, Readable Translation of St. Teresa of Ávila’s The Interior Castle

Informed by over forty years of contemplation, Teresa’s masterpiece on prayer displays the ultimate combination of spiritual experience, humility, and pragmatism, detailing a life marked by both the highest mystical gifts and the most grounded love for others.

“I've been purchasing and reading Modern Saints translations since I first saw them released. When I heard that St. Teresa of Avila's The Interior Castle was next to come out, I was so excited. My excitement was justified, as this book is wonderful!”

- William D., Book Reviewer

Explore Our Books

-

![A person holding a book titled 'Confessions: a modern translation' by St. Augustine, featuring a green pear with a bite taken out on the cover, near a window.]()

Confessions

St. Augustine’s honest, unfiltered account of love, longing, struggle, and unexpected grace.

-

![Book titled 'The Imitation of Christ' by Thomas à Kempis, translated by Peter Northcutt, placed on a dark wooden surface.]()

The Imitation of Christ

Thomas à Kempis' classic devotional on humble discipleship, guiding you to align your life with the heart of Christ.

-

![Person holding a book titled 'The Practice of the Presence of God' by Brother Lawrence, translated by Peter Northcutt.]()

The Practice of the Presence of God

Brother Lawrence’s short guide to simple spirituality, helping you live every moment in God’s presence.

-

![Book titled "The Pilgrim's Progress" by John Bunyan on top of a gray notebook and a brown folder, with a black pen resting on the notebook, all placed on a wooden surface.]()

The Pilgrim's Progress

An exciting take on John Bunyan’s adventurous allegory, inspiring you to journey boldly toward a life with God.

-

![On the Incarnation]()

On the Incarnation

St. Athanasius’ profound exploration of the mystery of Christ, revealing the transformative power of the Incarnation.

-

![A person holds a book titled "The Interior Castle" by St. Teresa of Avila, with a golden key resting on the cover.]()

The Interior Castle

St. Teresa of Avila’s spiritual masterpiece, guiding you on a journey to deeper intimacy with God within the soul's many chambers.

-

![Book titled 'Orthodoxy' by G.K. Chesterton with a gold apple on the cover, placed on a glass table next to a wooden surface.]()

Orthodoxy

G.K. Chesterton’s whimsical defense of the Christian faith, inviting you to embrace the wonder and truth of orthodoxy.

-

![A book titled "Dark Night of the Soul" by St. John of the Cross, translated by Peter Northcutt, is placed on a gray textured fabric surface.]()

Dark Night of the Soul

St. John of the Cross’ profound guide to spiritual transformation, leading you through the trials of faith into the light of divine union.

-

![Person holding a book titled 'The Rule of St. Benedict a modern translation' by St. Benedict, with an illustration of a stained-glass window on the cover, on a green upholstered surface.]()

The Rule of St. Benedict

St. Benedict’s timeless guide to monastic life, inviting you to shape your life around the rhythms of prayer, work, and community.

-

![Book titled 'The Way of a Pilgrim' on a shelf, with a prayer rope in front.]()

The Way of a Pilgrim

The unforgettable journey of a pilgrim who longs to “pray without ceasing.”

-

![Front cover of a book titled "La Práctica de la Presencia de Dios" by El Hermano Lorenzo, translated by Dr. Marlee Northcutt, published by Modern Saints.]()

La práctica de la presencia de Dios

Experience Brother Lawrence’s sage wisdom in this new Spanish translation!